Everyone's first management role comes with growing pains. I remember the awkward phase of taking my first people management responsibilities at a Series A startup back in 2011 and then again at Twitter a couple of years later. I joined a still private Twitter at 25 as an early employee going from IC to building and managing a team from the ground up responsible for 40% of European revenue over a 5 year period.

The learning curve from IC to Manager is challenging and during the evolution, your mindset and skill-set must graduate from high output IC to servant based leadership. It is not about you anymore nor is it about being the smartest person in the room whilst you’re held to a different standard that you don’t quite grasp immediately. You also think the skills that advanced your career to management are the same skills that will advance you to the next level bringing the very same hustle, values, and results-oriented mindset to running your team but you will be wrong.

The secret sauce is in a behavioral and value-based transition shifting from a ‘doing’ mindset to a ‘projecting’ mindset where you move from achieving results through others and not yourself but this is easier said than done particularly when the skills valued in this new paradigm like management empathy, motivation, coaching, leadership, and a people orientation are in the early stages of development.

I recently spent two weeks at Stripe in San Francisco with leaders from engineering, product, revenue, and operations on management and leadership best practices and it got me thinking about the mental models I’ve used for people management and the impact these have had on my approach to managing teams and people. Whilst these lessons are obvious to tenured managers I wanted to document them for newbie managers who were like me back in 2011 taking the plunge into a new world.

1. Optimize for internal locus of control

The theory of locus of control comes from clinical psychology developed by Julian B. Rotter dictating that individuals with an external locus of control are shaped by their environment whilst individuals with an internal locus of control shape their environment. In short, your behavior and response in any setting is such that you make things happen (internal) or things happen to you (external).

For effective self-management as a leader you must always optimize for internal locus of control as the environment you operate in will be ambiguous and present many obstacles you cannot control but will get easily distracted by. In practice things never go according to plan; that big deal in the pipeline is lost, a high-performer switches teams, a product bug impacts a date on the roadmap. All of this and more is par for the course in people management.

In my view, it is how you respond as a manager which reveals where you sit on the scale. A simple tool I often use when reflecting on my approach to any scenario is event + response = outcome. An individual with internal locus of control will recognize that an event has taken place and their response to it is what will inform the outcome whereas an individual with external locus of control will fail to adhere to this formula and look to others to follow conformity. At previous companies I’ve worked at I’ve observed this in high-stress environments where a team is under sustained pressure of high targets or reorg ambiguity where a team's role and place in the company changes.

This concept is also powerful in understanding the profile of your peers and direct team to develop coaching as a superpower. Logic dictates individuals with an internal locus of control are more resilient and adaptable so it's a manager’s imperative to coach for internal LOC behaviors across the business. You can change the outlook of a stressed team member very quickly by bringing them back to an internal LOC mindset or coach more effectively where you know an individual can bias towards external LOC. As a leader optimizing for internal LOC, the second-order effects are dramatic; your decision-making will be better, your leadership will be more adaptive, your results will be stronger.

2. Practice radical candor

The biggest driver of a manager's performance is coaching; how to give it, encourage it across the team and also receive it but the challenge is that coaching is broken in most startups where arbitrary cycles are put in place and there is manager hesitancy, to be honest with employees about their performance or even share it in platitudes. It happened to me! During my first year of management, I remember well how my default to being liked negatively impacted my style for sharing feedback.

This is the anti-goal and failure mode for a manager as if you want to be a good manager you need to first become a good coach. The challenge with being a good coach is that it is nuanced and the first hurdle most people fall at is how to give and receive information in the context of coaching; the purpose should always be for the coachee to improve with insight, this is the only purpose.

A framework I like to use in this context is the SBI-model where a manager explains situation, behavior, impact to a direct report to create better outcomes, decision making, and performance in the future. As an example ‘John I thought the pitch to the founder of XYZ today lacked charisma and storytelling resulting in you having less attention and weight in the room’.

In Kim Scott’s Radical candor playbook feedback should be HHIPP; helpful, humble, immediate, in-person and doesn’t personalize. So in the above example, you are focusing on the pitch and not John directly. The communication style is also important where it needs to come from a place of improving the performance of the coachee. As a manager reflect on the language you use - is it confrontational? Is it accessible? Is it authentic?

The sweet spot for communication is in the upper right quadrant of the communications matrix where you care personally and challenge directly to be radically candid. If you are unable to care personally this will be known in the relationship with your direct report so it is important you build this foundation for Radical Candor to be impactful.

3. Honor the coaching process

Coaching is a process. We’ve all been in a 1:1 or feedback session with a manager where insight is surfaced or an ask for feedback is made but the next time you hear about it is in your designated feedback cycle 6 months later. Coaching is a process and it must be structured and regularly revisited in this way for it to be valuable. As a manager, you are there to support and guide your team but you too will need a plan to usher through the developmental improvements you’ve spotted for your team. An effective framework I like to use in this context is the GROW model developed by Graham Alexander in the 80s which stands for :

* Goal

* Reality

* Options

* Way Forward I like the GROW model as it is designed to communicate a shared journey between manager and report to decide the destination, where they are now and how to get there. What I’ve found to be pivotal in this process is the establishment of a shared understanding of emotions and motivations in the reality phase where you can build a view on the intrinsic or extrinsic motivations of your team and how they feel in the here and now. Delivery of feedback in a timely manner is critical to the GROW model. Sense-check with your team how they like to receive feedback on these areas and on what cadence so you don’t overwhelm and it is constructive.

4. Speak your team’s language

As a leader, you are constantly oriented towards managing the performance of your team. How do you work with your team to ensure they are focused on the right tasks that offer them the most skills development and role satisfaction? Moreover, how do you motivate tenured high performing reports, tenured low-performing reports or low-performing new reports?

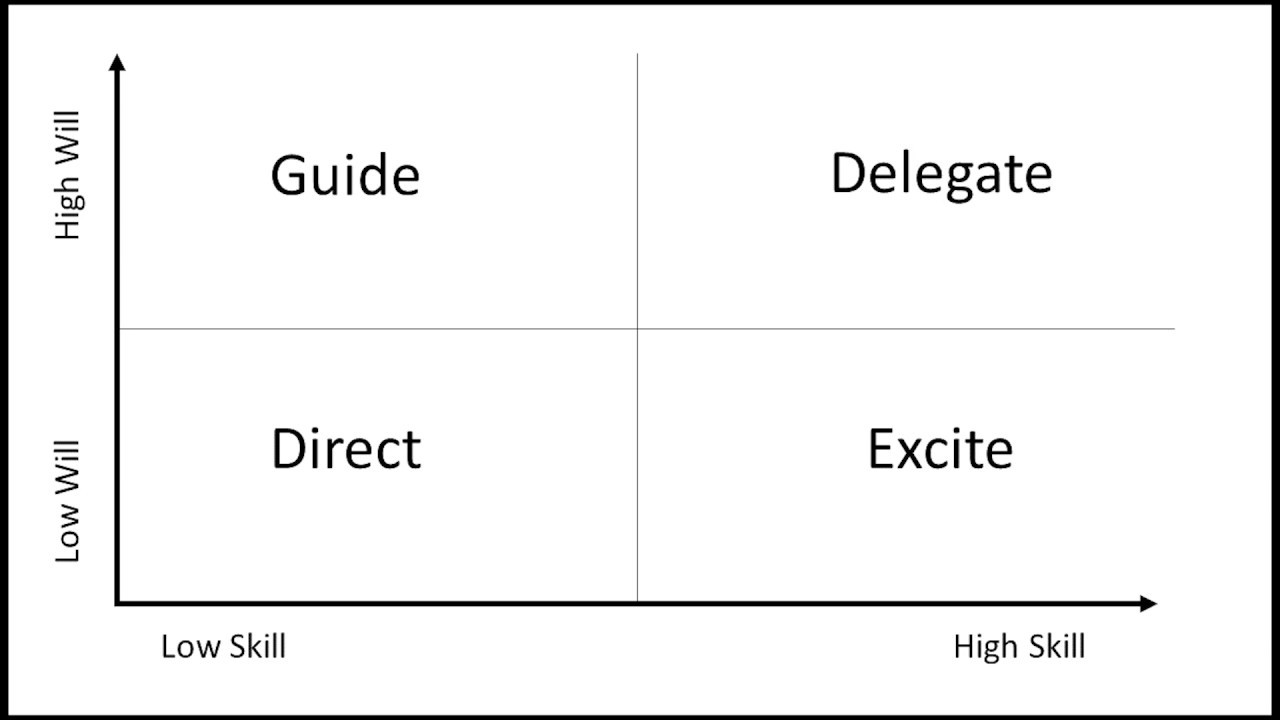

The answer to this question is made more difficult in that you have multiple personalities, interests, and motivations across your team so success lies in conceptually understanding what approach to take with each report given there is no one-size-fits-all approach. The skill/will matrix is a useful tool to visualize a person's skill-level and motivation-level for under-taking a task and the corresponding strategy a manager should employ to create a win-win scenario for the report and the task. Skill relates to capability and experience whilst will relates to motivation.

Step 1. Understand where your team sits in the matrix

A lack of understanding as to where your team sits in the matrix creates scenarios where you will be using foreign management techniques that simply don’t resonate. In my early management days, this was the most transformative technique I brought into my day to day practice. Up until this point, I found myself using similar motivation techniques to team members with high skill/high will and high skill/low will.

Step 2. Adjust your approach to reflect where your team is

Once you understand where your team is you can adjust accordingly. Your approach for Sarah who is 4 years in her role with high-skill/low-will is very different from Sandra who is one year into her role with low-skill, high will.

As a tip, take the time to go through this exercise it is easy to place your team in incorrect quadrants. This matrix is also fluid so your team will move around, don’t do them a disservice and both them into a quadrant in perpetuity.

5. Learn the art of delegation

The trapdoor for new managers is not creating sufficient distance between what made them successful in their old role and what is required to make them successful in their new role. Oftentimes new managers gravitate towards the old reward systems and tasks that helped them advance in their career creating scenarios where a sales manager begins to micro-manage inadvertently by staying too close to IC work where they feel like they can add immediate value instead of respecting distance and coaching from the sidelines.

This can especially occur when an IC moves to a management role with a pseudo-expectation from leadership that you will continue to provide value in this realm whilst managing the team. It’s a precarious line to walk as you risk the inability to graduate to the next leadership passage and remain in limbo whilst your team feels that you’re poking around in their work.

The key to managing this is ensuring you have a framework to help inform what work can be delegated away from your day to day whilst maintaining business continuity. Taking a simplistic view on this Jim Schlesker introduces a 70% rule which dictates that a manager should delegate a task where a team member can complete it to at least 70% as well as the manager can. In practice, I like Andy Groves’s task-relevant maturity approach where the individual’s maturity relating to a task is assessed before it is delegated split into low-TRM, medium-TRM, high-TRM.

The concept of task-relevant maturity isn’t at the individual-level. Individuals whilst highly capable may have high-TRM and low-TRM with different tasks. When a capable manager becomes a manager of managers their task-relevant maturity is low and they will require coaching where they didn’t require coaching as a Manager of ICs in the previous world. Likewise, when a high output IC is promoted into a senior lead role their TRM will be lower than what it previously was and will require coaching. Using the skill/will matrix you can directionally assess an individual's TRM and where they will sit in the TRM designation.

* Low TRM : structured, task-oriented, when, what, how.

* Medium TRM: Individual oriented, mutual reasoning.

* High TRM: Minimal manager involvement, agree on objectives and monitor.6. You are a change agent

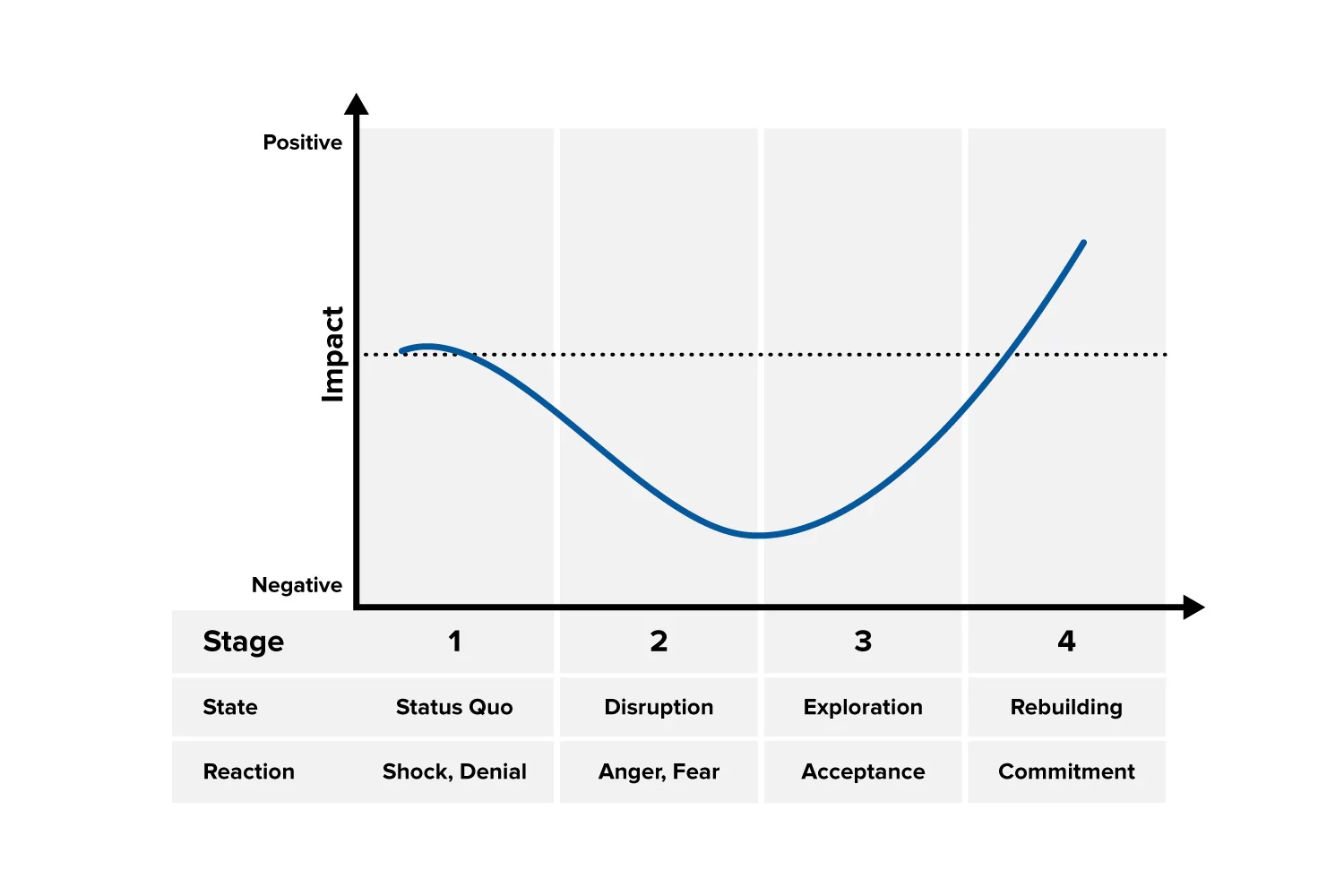

No organization is static, change is constantly afoot. Your role as a manager is to be a champion of change and create an environment where direct reports can be confident in the change that is occurring. Change over the course of a business has many forms from change in product direction, change in selling, change in customer focus, change in team or org structure. Knowing how to navigate change as a new manager will differentiate you as a manager and how you engage with your team.

Your competency is about coaching the team through organizational changes so that they maintain their effectiveness, buy-in, and satisfaction. During my time at Twitter, I led the EMEA integration of some teams we had acquired through an acquisition process to my direct team which was a jarring experience for ICs on both sides with ambiguity about the future. My main learning through this process is to over-communicate change, ensure it is understood and that ICs are supported.

To ensure change is managed well under your watch and smooth for the IC population zoom out and reflect on the big picture. Being able to manage the team response and journey over this timeframe is critical to your competency as a manager. You need to be able to see around corners sharing context with the business and leadership on both stages of change at leadership level and reaction to change at IC level.

The opportunity cost of not managing this effectively is significant with immediate first-order effects in a failed change management initiative and second-order effects on how this impacts other teams and culture in the org. A framework that I have found to be helpful is the Prosci change management methodology and its five levers. Whilst all are crucial parts of the puzzle I specifically want to call out two key levers as critical.

Communication is of utmost importance. I've learned the hard way that where you feel you have little to communicate you actually have more to communicate as a leader. Humans will fill the void and make assumptions where there is a lack of information on how change affects them. Equally team training for the day to day implications of change management is a critical integration lever for managers to establish a shared sense of belonging amongst impacted teams. Obviously there is a spectrum of severity of change but being able to lead change as a manager is a skill you need to develop.

7. Who’s got the monkey?

You will have many moments feeling like you’ve spent an entire day sorting out someone else's problems. Customer issues, team conflict, performance issues will pop up in every forum from 1:1s to team meetings and when they do you have an option to take responsibility or coach the team through to resolution. I’ve been in scenarios where I have felt like I’ve proactively chosen the coaching route but indirectly have assumed responsibility. Onken refers to this as ‘monkey management’ where a ‘monkey’ is a task that should be handled by a direct report but ends up with the manager creating a lack of space for managers to focus on ‘gorillas’ which are strategic tasks.

It’s sometimes hard to identify how you’re doing on this one but a good litmus test is to reflect on your week and how much of your time has been spent on coaching / strategic tasks or directly solving issues for your team. If you are indexing heavily on ‘monkey management’ you have a delegation and time management problem.

In practice this means you allow your team to pass issues to you and make them your problem. You are there as coach but your role is not to take ownership of day to day problems; you are also doing your team a disservice and robbing them of development opportunities to solve these on their own steam. Oncken suggests a bunch of strategies to deal with monkey management, the more salient ones are:

* Monkeys should be fed or shot

* Arrive at a decision early, do not waste valuable time on prolonging the issue.

* The monkey population should be kept below the maximum number the manager has time to feed

* It should not take more than 5 - 15 minutes to troubleshoot these issues

* Monkeys should be fed by appointment only

* Optimize for these issues in organized meetings like 1:1s

* Monkeys should be fed face-to-face or by telephone, but never by email

* Email simply adds to the feeding process and wastes time

* Every monkey should have an assigned next feeding time and an agreed-upon resolution outcome and date

* There should always be a next step with the direct report as the owner.The ideal outcome is that team-imposed time on solving day to day issues is minimized to a local minimum and strategic tasks are maximized to a global maximum.

8. Know your tribe

As you graduate to the next leadership passage of people management your set of stakeholders also evolves to become multi-constituent and cross-functional with the need to manage up and manage down. To become an effective manager you must build a community of individuals across different teams to be successful where you can have influence without positional power. As your role matures in an organization so too does the complexity of being productive and producing good work where you will be interdependent on other teams so having a managerial bias towards social systems is necessary to do great work.

Build relationships proactively and nurture them. An effective manager has access to the relationships and leaders needed by their team to succeed. Oftentimes new managers arrive in a role with little to no understanding of the peer communication practices at management level. Finding your place in this system isn’t a piece of cake so sometimes it's useful to carry out some stakeholder mapping and landscape analysis so you can manage stakeholders, leaders, and peers accordingly.

A framework I still go back to every now and again particularly with complex cross-functional projects is the power/interest matrix which helps inform a manager’s approach to stakeholder management at project level and organizational level.

What new managers get wrong about stakeholder management is the need to manage each stakeholder in the same way. In practice, every stakeholder’s interest and influence on a project will be different so ensure you are maximizing your energy in the most optimal way by proactively assessing the landscape and allowing the matrix to guide your approach.

9. Develop your people

As a manager, you will be judged on the development and retention of your people, their output and value-add to an organization. New managers often lack the skill and ability to handle career conversations so understanding a few concepts helps to provide credibility and trust your team. We’ve all had good career conversations and bad career conversations, trust me when I say your team will know the difference and if you are faking it. Start from an honest place and transparently align your goals with theirs; the main goal of development conversations is to help coach towards the intersection of your report’ skills and career ambitions.

Firstly, understand the differences between T-shaped careers vs I-shaped careers. T-shaped individuals optimize for breadth and depth of experience as a general athlete whereas I-shaped individuals optimize for deep experience in a role; picture your full stack-developer vs your PHP developer. How you coach these individuals and support their development will be different and sometimes T-shaped individuals want to focus on I-shaped careers and vice versa.

Secondly, identify a career framework and stick with this framework and development plan. A process I’ve been using for a long period of time is the combination of IKIGAI with OKRs which creates a shared understanding of motivations and emotions attached to an individual's development plan and a tangible path to achieve this in the form of measurable objectives.

How can I put this into practice?

As always practice makes perfect! Find a peer manager that you can share progress with and create a regular check-in with your direct manager. Putting these models into practice requires commitment but will pay dividends for your team’s growth over time.

* Communicate effectively - radical candor

* Invest in your people - SBI, GROW

* Know how to motivate your team - skill-will, trm

* Champion change

* Build a community

* Be ruthless optimize for gorillasIf you're interested I'd love to discuss more on Twitter you can reach me here.